|

Data and Automation

This topic used to be of concern only to the largest acquirers; however, technology adoption has advanced such that even smaller companies often operate on complex IT systems and leverage automated workflows for many business processes. As such, an understanding of the systems and data architecture of the parties is now both a key aspect of a thorough due diligence process, and a key structural consideration when selecting a TOM for all types of M&A. It is important to note that many large enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, such as SAP or Oracle, are highly configurable and thus can be extensively customized by the installers. It is almost certainly a mistake to assume that because “both of us are on SAP” that your data structures are in any way compatible! Let’s look at an example: Target Company's General Ledger Account Numbering Logic is described as AB.CDE.EFGHI And: AB=country CDE= legal entity FGHI= general ledger account number Acquirer's General Ledger Account Numbering Logic is described as AB.C.DE.FG.H.IJKL And: AB= legal entity C= country DE= division or business unit FG= budgeting cost or profit center H= tax treatment for this account, often used for feeds to "bolt-on" tax calculation engines IJKL= general ledger account number Right away we can see that in order to do joint reporting, we are going to need to do some breaking apart and re-mapping of the target’s data, or else forego same and institute a manual process. (Side note- if we use outsourcing, any such manual process would likely require a new contractual agreement, since the current process for reporting leverages the existing acquirer data structure). Given the integrated nature of these tools it is common for multiple processes to share a single data field-even across multiple functions or even business units. Recall that the acquirer had a tax treatment field designed to export data to a tax engine. Such a field would often be used in the USA to send data to separate tools for sales tax and income tax, and outside of the USA might be used for both value-added tax (VAT) and for local financial statement reporting under that geography's GAAP rules. The field may also be used to exempt certain accounts from consideration in the budgeting process, i.e. to indicate accounts used only for intercompany transactions. Bottom line, be sure you have a complete understanding of the data map and the design of all interfaces and workflows before planning to change an existing data structure. Here I’ve provided the more difficult example, where the target’s existing data needs to be broken into smaller segments. This is more common since the acquirer is usually larger and more technologically sophisticated than the target; however, the opposite situation could also apply. In that case the exercise may be simpler, i.e. you can combine data more easily than you can split it out. In either case, you must take into consideration the time and resources required to consolidate on a combined toolset, and that will have an impact on your selected TOM. Note also that we’ve only looked at GL account structure in our example thus far. Imagine the scope that can occur across all of the parties combined data elements and data sets! This is the reason that data migration is often the “long pole” on the integration critical path, and why an understanding of data and systems architecture is a key consideration in TOM selection.

0 Comments

By now you should have a good idea of how to design or adapt a Target Operating Model given the structure of your deal or deals, and your company’s propensity to acquire. The next step is to evaluate whether your chosen TOM is impacted by aspects of your company’s structure.

Shared Services Impacts For our purposes let’s define shared services as centralized administrative groups, usually located in low-cost jurisdictions, that perform back-office activities for much or all of the enterprise using an employee model. Whew- that was a mouthful, but the key phrase for TOMs is “using an employee model”. This generally means that acquirers have sufficient span of control over the shared service organization to adapt it to the needs of the integration. And indeed, most adapt fairly well so long as sufficient time and budget to achieve are provided. To assess the budget and timeline requirements certain key aspects should be considered:

Outsourcing Impacts Outsourcing is similar to shared services, except the activities are performed by third parties under contract rather than employees, and thus the span of control is limited. If either or both the buyer and seller use outsourcing, expect substantial time and additional costs to achieve the desired TOM due to the need to create new service contracts for the extraordinary activities resulting from the transaction. Try to get access to any outsourcing contracts early in M&A diligence- even if a clean room is required- so as to get a head start on the process of identifying the scope of required that will be required for TOM achievement. Also, be sure to consider capabilities of outsourced staff, and be aware that most outsources are reluctant to be flexible with regards to interim or exception processes. This means that more time will be required up front to design and standardize a process, enter into a contract to have the outsourcer perform the process, and train the outsourced staff. You will want to develop an integration plan that minimizes the number of transitions, which can be particularly challenging if your value drivers call for an interim TOM. Regardless, any TOM you plan to achieve will have to be well-defined and validated in advance, and you need to be prepared to operate in that model until the next well-defined transition can be executed- usually at least a few months. Bottom line: if either party uses outsourcing, you can anticipate less iterative flexibility and higher costs for TOM achievement than you would experience in a shared services model. If acquisitions will be a recurring component of your growth strategy, you may benefit from creating some standardized TOMs to more quickly assess deal scope and costs. How many, and what kind, will depend on your industry, and the variety of deals you plan to do.

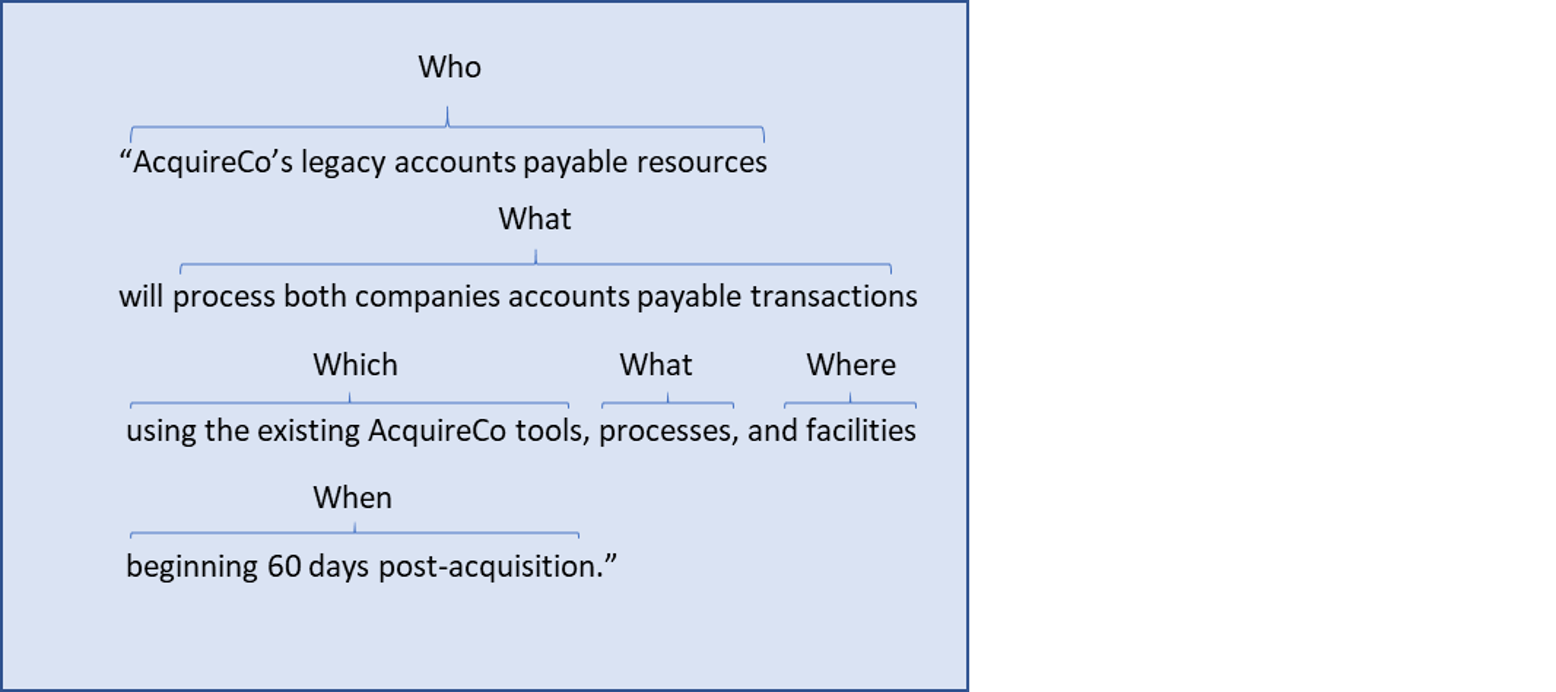

Components of a Standardized TOM Recall that a TOM describes the “5 W’s” or Who will do What from Where on Which tools, When. In preparing standardized TOMs, it is possible to address these questions, as well as to add some additional parameters that make integration planning, estimating, and execution more repeatable and efficient. The following components should be considered for incorporation into a standardized TOM:

Note that while it is possible to create a quite sophisticated model if all of the components above are included, it is most likely only cost-effective to do so if many acquisitions are planned. Furthermore, in-house knowledge of the appropriate estimating factors, task lists, etc. will be limited unless several acquisitions have already been executed, or unless you conduct a program to determine these inputs. The effort and complexity of the standardized TOM is why most companies continue to use business cases to evaluate synergy and cost realization efforts. That said, it is possible to document standard TOMs that include only non-quantitative data, and this may also be of some use. Minimum TOMs Your minimum TOM should be just that. It should describe the minimum level of integration required to meet your legal, regulatory, and non-negotiable corporate policy requirements, i.e. public companies will have consolidated financial filing requirements. Regardless of whether you want to delve into the creation of sophisticated models, creating a minimum TOM is usually a very informative exercise. It engages the executive team in decision making to decide the non-negotiables, and then provides those decisions as established parameters for future transactions. It will also highlight key dependencies that may have been previously hidden. For example, if email integration is imperative due to the use of email for emergency notifications, investigate whether network integration is required as a facilitator for email integration. It is not uncommon for these critical path items to manifest and create a quite extensive minimum TOM. Insights into how extensive the minimum integration requirements will inform your decision process, both in regards to what kinds of deals you should pursue, and also what internal initiatives should be explored if acquisition is to remain a key component of your growth strategy. Recall that we discussed in previous chapters how back office structure impacts TOMs? If you plan to grow by acquisition and use extensive outsourcing and/or automation in your back office, you will have a more involved minimum TOM due to the high number of dependencies in such a model. In this case you could consider deciding to restructure the back office to add in additional flexibility to accommodate acquisitions. Alternatively, you could adjust your valuation models to accommodate higher costs to achieve, recognizing that doing so may reduce the number of deals in which you will be a competitive bidder. Either way, the minimum TOM exercise brings these choices out in the open, where they can be considered and addressed. If your company needs to do innovative or extra-accretive transactions routinely, then it will be critical to have a defined minimum TOM, and to ensure that your back office has the flexibility to accommodate these transactions. Full Integration TOM In a full integration TOM the acquired company disappears, and the acquirer’s model has the same 5w’s as it had prior to the transaction. Simply put, it describes the model whereby the acquirer completely absorbs the acquired into their standard organization design, tools, processes, and facilities. There are two critical points to remember when it comes to full integration TOMs. First, if you have extensively used outsourcing and automation there may be little difference in your minimum and full integration TOMs. This may indicate that you can realize value only from deals that will be fully integrated. It follows, then, that deals that rely on extra-accretive revenue synergies would not be a good fit. Companies in this position are largely limited to overlapping and some types of complimentary deals and must use other strategic transactions to achieve innovative growth. Second, the cost of integrating an acquired company into your existing target operating model will bear no resemblance to the current run-rate costs. This may sound obvious, but I continue to see deal models that assume existing run-rate costs, or run-rate plus an escalation factor, perhaps computed as a percentage of accretive revenue. Either approach completely ignores the costs of actually executing the integration program. We will go into the calculation of costs to achieve in more detail in later posts. It takes a substantial effort to prepare a full integration TOM that includes all of the components discussed at the beginning of this post; however, for the serial acquirer the investment is worthwhile. A properly designed full integration TOM can dramatically reduce the time it takes to fully integrate, aid in calculating costs to achieve for valuation purposes, reduce integration program costs, and provide program-wide visibility into the critical path and dependencies. Furthermore, this model is easily converted into a standard workplan and baseline program budget, both of which can then be “rolled up” with similar documents for other acquisitions, providing enhanced management visibility. Partial Integration TOMs If your back office has a flexible structure, and you plan to do a variety of deals, it can also be useful to define some standard partial integration TOMs. For example, at one prior client we employed 2 partial integration TOMs in addition to our full and minimum TOMs (for fun we referred to these as the Party Sub, the Footlong, the 6-Inch, and the No-Soup-For-You). The difference between the 2 partial TOMs largely hinged on whether the acquired company would be integrated into the parent company’s IT network, since network integration was required to access many of the standard tools and programs such as email, benefits, and procurement. With the 4 models defined, and estimating tools in place for each, we could very rapidly estimate the effort-hours, timeline, and costs for deals using a standard tool, and incorporate this information into the deal evaluation. Also, by using the same tools each time, we were able to identify areas where the models needed adjustment and thus improve them over time. Recap Standard TOMs are a useful tool for any company that plans on routinely using acquisitions as part of its growth strategy. Preparation of standard TOMs will discover critical path dependencies, as well as inform management about the ability of the current back office structure to accommodate each deal type. Last month we introduced the concept of selecting a target operating model, or TOM, based on the parameters of the deal. In this month’s post we’ll take a deeper dive into how this would apply to a vertical transaction, such as AT&T’s proposed purchase of Time Warner, Inc. Recall that we previously stipulated most acquirers will lack the knowledge, tools, and relationships to effectively manage a vertical acquisition. As such, most vertical deals will require lower levels of integration until enough internal expertise can be developed to make effective choices about how (or whether) to combine the companies. This means the acquirer is likely to have both an interim and an end-state TOM. The interim TOM describes a stable point in the integration where the companies will “pause” integration, operating in that TOM state until such time as additional integration becomes appropriate. Of course, if the businesses are different enough, it may never be practical or appropriate to integrate fully, in which case the end-state TOM becomes minimal integration, and an interim model is not required; however, in this case the overall return on the deal is at risk. The valuations of most vertical deals rely on either extensive cost or extra-accretive revenue synergies to justify the purchase price, and these synergies can be very difficult to achieve when companies continue to operate as separate entities. In the case of AT&T’s proposed purchase of Time Warner, Inc. it seems unlikely that AT&T’s internal organization design, systems configuration, and capital allocation cycle are ideal for media content production. AT&T has no content production expertise. Nor do they have any of the valuable relationships on which media producers rely. Some integration will be required to meet the minimum compliance requirements, such as being able to file SEC reports. And there may be some low-hanging fruit, i.e. standardizing on a common payroll provider and/or employee benefits platform, laying off some administrative employees, squeezing a few common suppliers for lower costs, but largely I would anticipate the companies continuing to operating independently should the deal come to fruition. What then will that mean in regards to AT&T realizing the synergies from the acquisition? Let’s first consider a simplified example with two imaginary companies. Cones, Inc. manufactures cones which it sells to its only customer Cream, Inc. an ice cream manufacturer and retailer. Prior to combining their business results are as follows:

Cream, Inc. decides to buy Cones, Inc. to reduce input cost for cones in their ice cream parlors. Comparable companies are selling for 10x revenue, so the purchase price of Cones, Inc. would be (200 x 10=2000). Since Cream, Inc. lacks the knowledge and equipment to make cones, they decide to let Cones, Inc. stand alone. After the acquisition operating results would be:

Cream, Inc. gets a boost in operating profit from $300 prior to the acquisition to $350 ($500-$150) after the acquisition. The combined results do not change since the operations are the same as before the combination; furthermore, Cream, Inc. must recover their cost of acquiring. If they wish to recover that cost over 5 years, they would need ($2000/5=$400) in benefits per year. This of course assumes that attorney fees, bankers, auditors, and other transaction costs were zero, and also ignores the time value of money. Even if Cones, Inc. had additional profitable customers, we would still have only accretive synergies if we persisted with maintaining separate operations, and the valuation would have been proportionately higher.

Now consider this example in light of AT&T’s proposed valuation for Time Warner, Inc. of 3.7 times revenue, and 27.8 times earnings, and it should become apparent that my bias against vertical deals is not merely the result of irrational prejudice. The bottom line is that unless a profitable business is being very inefficient in its operations or has a high cost of capital it is very difficult to realize extra-accretive synergies at all. Such synergies come from combining either cost structures or market offers, and often this is just not practical. Vertical deals will still take place, and AT&T’s consideration of Time Warner as a defensive move against Comcast’s acquisition of Universal is an example, but for most business vertical deals should be approached with a high degree of skepticism. The difficulty of combining non-overlapping businesses will likely delay synergy realization, and the purchase price, combined with costs to achieve extra-accretive synergies, make these very tricky indeed. Introduction Last month’s post wrapped up our “Deciding to Acquire” category for 2018. This month we’ll begin a new series of posts entitled “Selecting Target Operating Models” where we’ll explore how to choose our approach to integration based on deal parameters. Definition: Target Operating Model A Target Operating Model, or “TOM” describes the interim or end-state of both the acquirer and the target post acquisition. A well-crafted TOM describes the “5 W’s” as laid out in the following question: Who will do What, from Where using Which tools, and When? In this structure the “who” describes the personnel pool. Will it be legacy target staff, legacy acquirer staff? Both? Neither (i.e. we are eliminating the positions and outsourcing)? The “what” describes the business processes to be executed, including any net new processes, and/or adaptations of legacy processes. “Where” indicates the facilities where the resources (the “who”) will work, while executing each process (the “what”). Again, facilities may be legacy acquirer, legacy target, or net new. “Which” indicates the tangible and intangible assets used in the post-deal environment. Are we consolidating on a common enterprise management system? Are we going to continue operating on legacy contracts, or will we attempt to novate or otherwise establish common contractual agreements? Finally, “when” indicates the time period where the target operating model begins and ends. Many deals will integrate directly into their end-state operating model; however, there can also be cases where both an end-state and an interim model are appropriate. In this case, the “when” will describe when the interim model ends, and the end state model begins. Putting all this together, we get assumptions for each workstream that sound something like this: Such TOM sentences become important assumptions about the deal. For example, it would be reasonable to assume from the example above that we can anticipate synergies from the elimination of the target’s accounts payable team, the facilities they work in, and the tools they use, but we will also have:

Deal Rationale Considerations and TOM Selection Recall from February’s post that we identified 2 basic categories of deals:

As we stipulated previously, these categories are highly generalized for purposes of this discussion. Additionally, it is common for acquirers to anticipate both cost and revenue synergies for a given transaction; however, one of these will, in fact, be what we call the primary value driver, meaning that this synergy addresses the strategic deal rationale. Overlapping deals will usually optimize at full, or nearly full, integration. This is because a greater degree of integration scope generally maximizes cost synergies by providing for the elimination of duplicate “W’s” (who, what, where, which) per our “5 W’s” model. Additionally, revenue synergies tend to be either unaffected or even optimized at higher levels of integration. For example, additional revenue synergies could result from cross-selling, raising prices, bundling offers, etc. The greater the overlap between target and acquirer, the more this tends to hold true. Complimentary deals have much greater variability in optimal TOMs, but there is a general rule that can be applied: The greater the level of innovation or creativity implicit in the revenue synergies, the lower the level of optimal integration The table below provides a general outline of where most complementary deals will optimize:

Many companies underestimate the challenges with learning to operate in new geographies, and university case studies are full of such examples. If geographic expansion is the primary driver of deal rationale, the best approach is usually to do a minimum amount of integration initially, and to stabilize on an interim TOM. This allows the acquirer’s management to focus on gaining share in the new market and achieving the revenue synergies, without the distraction of adapting back office systems and processes to adequately address any new compliance or operating requirements. Furthermore, retaining the acquired in-country staff allows the acquirer to benefit from their local knowledge and networks.

Portfolio expansion deals usually benefit from moving straight to full integration, provided that the products being added have reached a level of maturity where innovation is not a primary concern. Integrating fully facilitates joint management of product and offer portfolios, and thus helps with revenue synergy realization. And of course, as with all full integration TOMs, and available cost synergies will also be realized. Innovative deals are a real challenge for most companies, particularly public companies with heavy compliance requirements. The temptation to integrate- and thus realize cost synergies while simplifying back office processes- will be difficult to resist. Just know that the track record of companies that integrate their innovative acquisitions is poor indeed. Key talent gets recruited away, disruption in tools, processes, benefits, or facilities creates a distraction that hampers the innovative process. Upon integration the combined company often looks a great deal like it did prior to the deal, with no noticeable increase in innovative capabilities. Correspondingly, the same pitfalls apply to acquisition of immature product offers that still require “care and feeding” from their development teams. Bottom line: if you are lucky enough to buy a goose that lays golden eggs, resist the temptation to remodel her nest! Conclusion Choosing the right TOM is a vital component to crafting a realistic approach to due diligence, valuation, and synergy realization. Over our next few posts we’ll continue to expand on selecting and formulating TOMs for different deal types, and we’ll explore how various corporate structure and operational considerations impact our choice. We look forward to hearing your thoughts, K |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

Sign up to receive a free 30 minute consultation and our "PMO in a Box" toolkit!

|