|

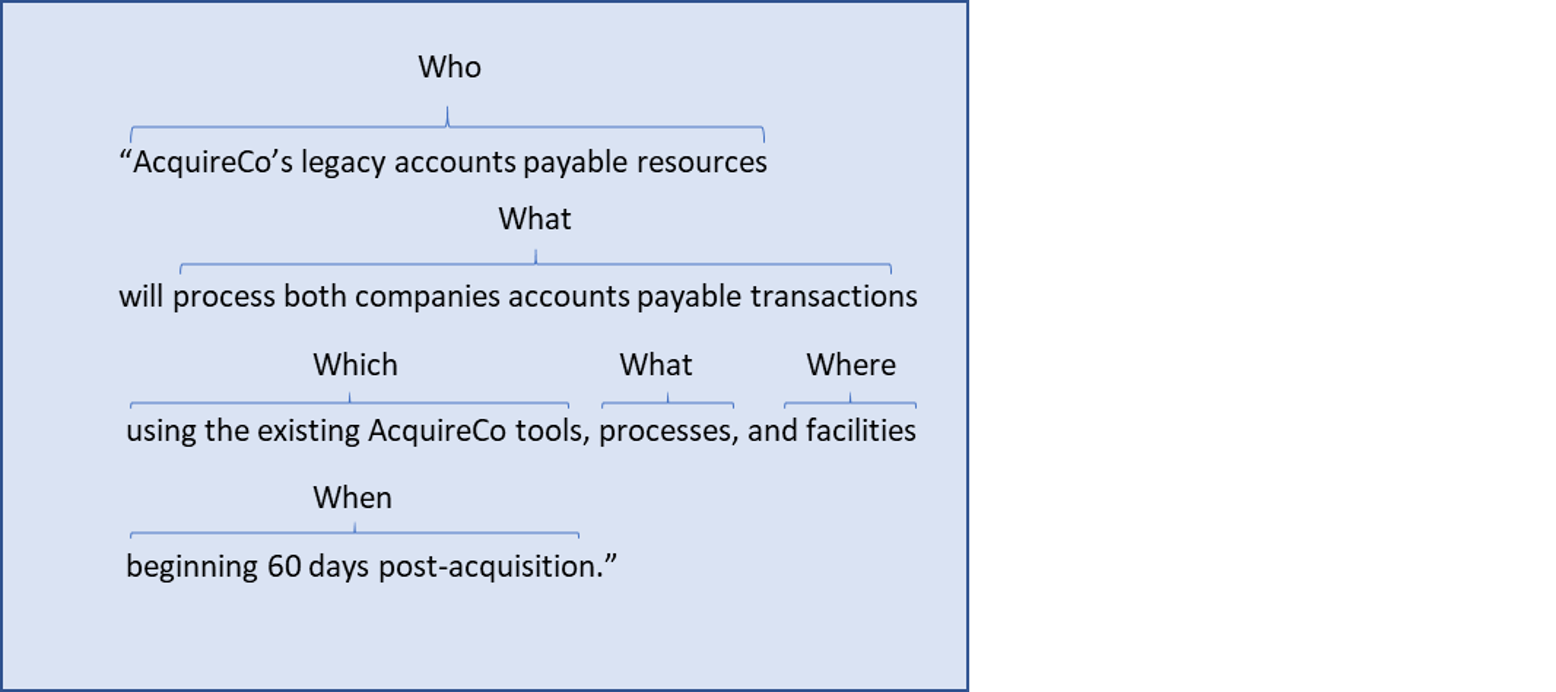

Introduction Last month’s post wrapped up our “Deciding to Acquire” category for 2018. This month we’ll begin a new series of posts entitled “Selecting Target Operating Models” where we’ll explore how to choose our approach to integration based on deal parameters. Definition: Target Operating Model A Target Operating Model, or “TOM” describes the interim or end-state of both the acquirer and the target post acquisition. A well-crafted TOM describes the “5 W’s” as laid out in the following question: Who will do What, from Where using Which tools, and When? In this structure the “who” describes the personnel pool. Will it be legacy target staff, legacy acquirer staff? Both? Neither (i.e. we are eliminating the positions and outsourcing)? The “what” describes the business processes to be executed, including any net new processes, and/or adaptations of legacy processes. “Where” indicates the facilities where the resources (the “who”) will work, while executing each process (the “what”). Again, facilities may be legacy acquirer, legacy target, or net new. “Which” indicates the tangible and intangible assets used in the post-deal environment. Are we consolidating on a common enterprise management system? Are we going to continue operating on legacy contracts, or will we attempt to novate or otherwise establish common contractual agreements? Finally, “when” indicates the time period where the target operating model begins and ends. Many deals will integrate directly into their end-state operating model; however, there can also be cases where both an end-state and an interim model are appropriate. In this case, the “when” will describe when the interim model ends, and the end state model begins. Putting all this together, we get assumptions for each workstream that sound something like this: Such TOM sentences become important assumptions about the deal. For example, it would be reasonable to assume from the example above that we can anticipate synergies from the elimination of the target’s accounts payable team, the facilities they work in, and the tools they use, but we will also have:

Deal Rationale Considerations and TOM Selection Recall from February’s post that we identified 2 basic categories of deals:

As we stipulated previously, these categories are highly generalized for purposes of this discussion. Additionally, it is common for acquirers to anticipate both cost and revenue synergies for a given transaction; however, one of these will, in fact, be what we call the primary value driver, meaning that this synergy addresses the strategic deal rationale. Overlapping deals will usually optimize at full, or nearly full, integration. This is because a greater degree of integration scope generally maximizes cost synergies by providing for the elimination of duplicate “W’s” (who, what, where, which) per our “5 W’s” model. Additionally, revenue synergies tend to be either unaffected or even optimized at higher levels of integration. For example, additional revenue synergies could result from cross-selling, raising prices, bundling offers, etc. The greater the overlap between target and acquirer, the more this tends to hold true. Complimentary deals have much greater variability in optimal TOMs, but there is a general rule that can be applied: The greater the level of innovation or creativity implicit in the revenue synergies, the lower the level of optimal integration The table below provides a general outline of where most complementary deals will optimize:

Many companies underestimate the challenges with learning to operate in new geographies, and university case studies are full of such examples. If geographic expansion is the primary driver of deal rationale, the best approach is usually to do a minimum amount of integration initially, and to stabilize on an interim TOM. This allows the acquirer’s management to focus on gaining share in the new market and achieving the revenue synergies, without the distraction of adapting back office systems and processes to adequately address any new compliance or operating requirements. Furthermore, retaining the acquired in-country staff allows the acquirer to benefit from their local knowledge and networks.

Portfolio expansion deals usually benefit from moving straight to full integration, provided that the products being added have reached a level of maturity where innovation is not a primary concern. Integrating fully facilitates joint management of product and offer portfolios, and thus helps with revenue synergy realization. And of course, as with all full integration TOMs, and available cost synergies will also be realized. Innovative deals are a real challenge for most companies, particularly public companies with heavy compliance requirements. The temptation to integrate- and thus realize cost synergies while simplifying back office processes- will be difficult to resist. Just know that the track record of companies that integrate their innovative acquisitions is poor indeed. Key talent gets recruited away, disruption in tools, processes, benefits, or facilities creates a distraction that hampers the innovative process. Upon integration the combined company often looks a great deal like it did prior to the deal, with no noticeable increase in innovative capabilities. Correspondingly, the same pitfalls apply to acquisition of immature product offers that still require “care and feeding” from their development teams. Bottom line: if you are lucky enough to buy a goose that lays golden eggs, resist the temptation to remodel her nest! Conclusion Choosing the right TOM is a vital component to crafting a realistic approach to due diligence, valuation, and synergy realization. Over our next few posts we’ll continue to expand on selecting and formulating TOMs for different deal types, and we’ll explore how various corporate structure and operational considerations impact our choice. We look forward to hearing your thoughts, K

0 Comments

|

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

Sign up to receive a free 30 minute consultation and our "PMO in a Box" toolkit!

|